Learn to solo with my jazz eBook

Learn to solo : chapters 6-10

I’m not making out that you can learn to solo just by studying my new eBook How To Solo, but it will certainly lead you on the path to creative improvisation.

Click here to purchase all 4 of my eBooks

Here are some extracts from chapters 6 – 10 to help you learn to solo.

Learn to solo chapter 6: Rhythmic variation

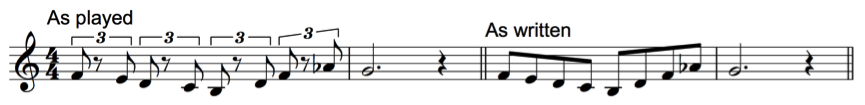

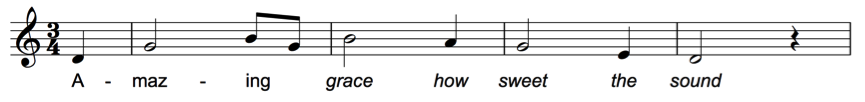

Throughout this series, I’ve repeated that the rhythmic core of jazz is swung eighth notes. I explained the theory of swing 8s in book 1, chapter 4. The feel of swing 8s derives from 8th note triplets, but with a rest on the middle note of each triplet.

It could be said that this jazz feel combines two time signatures: 4/4 and 12/8, hovering between the two.Written jazz implies this 12/8 feel but represents it on the page as ‘straight’ 8s.

Fig 74

There is no correct way to play swing 8’s. Bill Evans plays them more smoothly than, say, Hampton Hawes, but both these musicians swing. Your way forward is to listen.

(As I said in the author’s note at the start of this book, all examples should be played with a swing 8 feel unless otherwise stated.)

While you’re improvising, be constantly aware of this continuous stream of swing 8s, whether you play these notes or not. It’s as though you dip into them when required; they are always on hand ‘in the ether.’

Learn to solo Chapter 7: All Of Me

In book 3, chapter 9, I listed standards that jazz musicians need to know, and All Of Me probably ranks in the top 20. This song was composed by Gerald Marks in 1931 and has been sung and played by just about everyone.

The form of All Of Me is AB and has a length of 32 bars.

A = 16 bars

B = 16 bars

- In the early 60’s, when I used to earn money playing piano in the East End pubs of London, it didn’t take long before a punter would be on the bandstand, asking if I knew All Of Me. In those days, I would pretend to know whatever tune they requested, partly because I had a good pretty good ear, but mostly because they were often too drunk to notice whether I was playing the right chords!

Identifying key centres

There are just two simple steps required in order to locate a key centre:

- Locate each dominant 7 chord.

2 If the chord points towards its tonic, then you have located a key centre.

Analysis

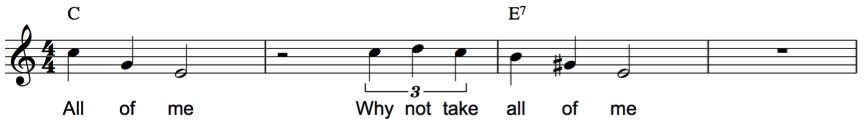

Chords 1 and 2 of All Of Me are giveaways, simply because the notes of the tune spell out each triad.

Fig 92

We’ll now focus on the movement of these two chords.

Learn to solo Chapter 8: 3s and 7s

In previous books, I’ve stressed the importance of locating the 3s of each chord and then linking them together via a track common to both chords.

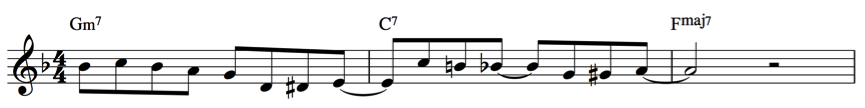

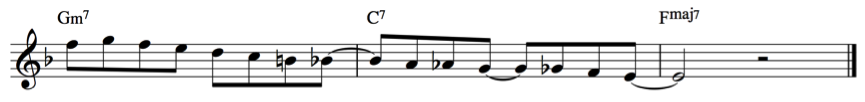

Fig 104

The same applies to linking 7s.

Fig 105

I have described this technique as ‘walking 3s and 7s.’ Refer back to book 1, chapter 11, for a refresher on this topic. Being aware of 3s and 7s within a chord and the tracks that connect them will enhance the harmonic journey of your solos.

In this chapter I’m going to take a different approach. The focus remains on 3s and 7s, but rather than walking from one chord to the next, we will now be linking these 3s and 7s within the same chord.

Chapter 9: A Berlin classic

In this chapter, I’ll be using the chord chart of Irving Berlin’s How Deep Is The Ocean

I recommend that you begin by listening to recordings of this beautiful song.

In book 3, I suggested that you first listen to ‘straight’ versions to familiarize yourself with the melody and lyrics. Billy Holliday’s version will be of no help initially, as she is improvising from the start, whereas Ella Fitzgerald and Julie London deliver an accurate rendition of the tune.

This also applies to instrumentalists. Bill Evans provides us with very little of the tune. Ben Webster and Stan Getz play much of the melody but are already bending it around before they’ve played the 32 bars. Coleman Hawkins uses the melody merely as a reference point and is telling his own story from the outset.

If sight-reading isn’t your strong point, knowing the lyrics of a song helps, particularly with rhythm.

So, when playing the first two bars of this tune, you might do one of the following:

1) Read the music, in which case you will see a rest followed by a quarter note, then a quarter note triplet, a barline, a quarter note and a half note.

2) Hear the sung words in your head:

beat… How much-do-I love you.

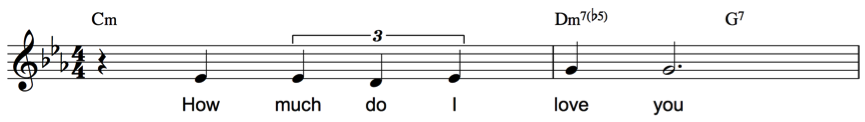

Fig 112

The key signature has three flats, but it is evident from the chord sequence that we are setting out in the key of C minor.

As we’ll later discover, the song ends in its relative major: Eb.

Chapter 10: Finding the sweet notes

When writing a tune, the songwriter looks for notes that stand out on the strong beats. When these chosen notes are brought out into the spotlight, they need to be making a statement worthy of their momentary prominence. If working from the diatonic scale, there are seven notes from which to choose.

As I’ve said before, when improvising, we are, in a sense, writing a new tune in the moment. As jazz musicians, we are composing on the spot so learn to solo creatively.

The most forceful statement is note 1: the tonic. The British National Anthem states its case pretty assertively by kicking off with two of them.

Fig 118

Running a close second behind the tonic is the dominant. We are now well aware of the relationship between tonic and dominant:

- V backs up I

- V leads to I.

How many songs start like this?

Fig 119

A more sensual note is 3. Chopin, perhaps the most romantic composer of them all, begins his Nocturne in Eb major as follows:

Fig 120

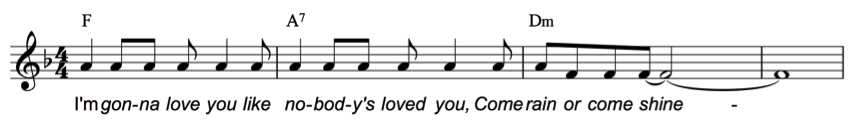

Harold Arlen repeats the 3 through his first phrase of Come Rain Or Come Shine. Notice that although the pitch is maintained in bar 2, it now functions as the tonic of III7.

Fig 121

Click here to purchase my eBook ‘How To Solo.’

And you can click here to subscribe to my online jazz piano course.