Stop playing jazzy. Start playing jazz!

Are you playing jazz or just playing jazzy?

Here is the third in my series of articles for the website ‘All About Jazz’

I concluded my last article in this series about playing jazz with a piece of advice handed to me by one of my old jazz piano teachers: ‘Don’t try to play jazzy.’ I’d now like to explore this statement and demonstrate how it affects my own teaching.

In the 70’s I played keyboards in what was known as a ‘jazz rock band’ and people often described my playing style on Hammond organ as ‘jazzy.’ In hindsight I would say that my band had little to do with jazz or that my playing was little more than ‘jazz tinged.’ This is no reflection, good or bad, on the band or my playing. But in retrospect, I now feel that what we were doing had little connection with what I now think of as jazz. In those days I was listening to lots of great organ players like Jimmy Smith and Jack McDuff, but I suspect that I was just trying to mimic them rather than striving for something that expressed my own creativity. Of course we all have to start somewhere and, hopefully, their influence gradually rubbed off, leading me away from just making jazzy sounds.

At this point, the temptation to make a stab at defining jazz is not a subject I wish to pursue, as our historic concept of jazz has now morphed into so many other types of music (which is surely a good thing) that the original meaning of the word has become blurred. I suppose one could list various attributes to a traditional concept of jazz and say that it involves improvisation, it swings (see my take on this in previous article), is often instrumental and usually has a structure and chord sequence.

A jazzy chord when playing jazz

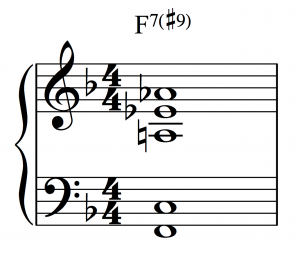

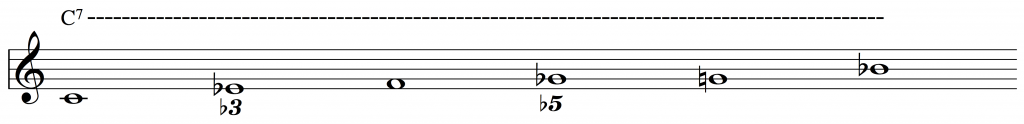

This brings me to my task of trying to separate playing jazz from just sounding jazzy. When I’m teaching, a student will ask me to show them a lick or chord I’ve just played. If there were a top 10 chart for most requested chord, here is number one:

This is the Jimi Hendrix ‘Purple Haze’ chord, it features in Come Together by the Beatles, and you’ll have also heard it in countless funk tunes. And, indeed, it is pretty funky. Now, I have nothing whatever against this chord. My point is this: I believe that the improviser (or composer/songwriter) needs to be aware of how a chord functions rather than simply using it for its own sake. Unless the entire composition or solo is based solely around one chord, just to play it in isolation purely because of its attractive sound can be a meaningless gesture that has no relevance in the bigger picture. Rather, we need to examine how each chord relates to its neighbour. Only then does jazzy become jazz.

So first of all, what is this chord? Well, it’s a dominant 7 topped with a sharp 9. In most musical instances a dominant 7 has a function: it either leads to or wants to lead to its tonic. But in the two songs mentioned above this is not the case, as in these instances the dominant 7 is acting as a tonic chord. In other words, it’s a non-functioning chord: It can stand in its own right or move to anywhere it chooses. A good example of non-functioning dominant 7 chords occur in a basic 12 bar blues.

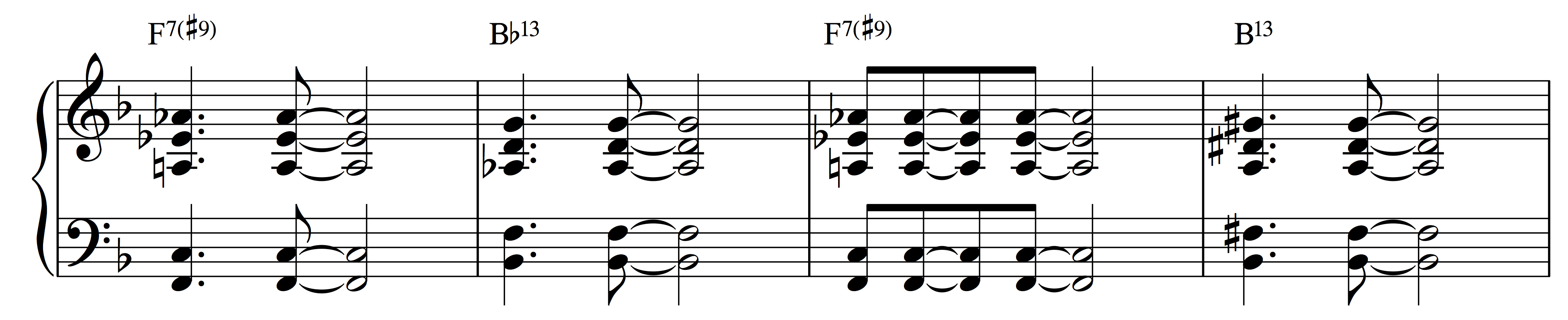

Here are bars 1 – 4 of a 12 bar blues comp. (Bar 4 contains the tritone substitute of F7).

For soloing, you could take a horizontal approach (one scale played over a group of chords) and use F blues scale.

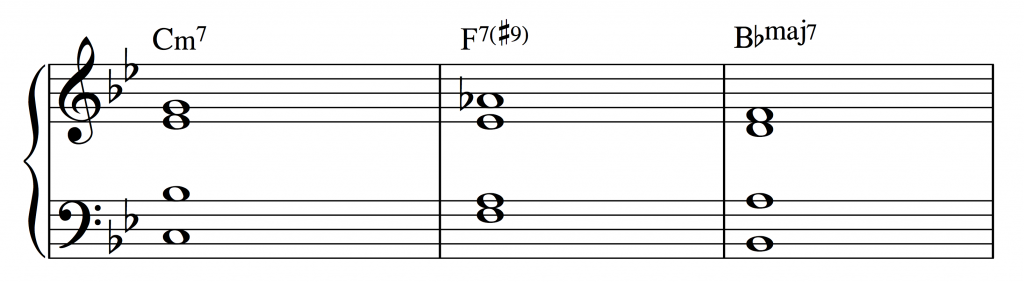

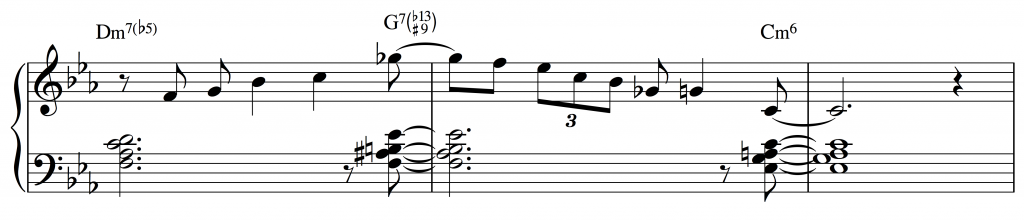

If the above illustration is an example of this F7(#9) when doing its duty as a non-functioning dominant 7 (not pointing to its tonic) how does the same chord look when performing its usual duties: i.e. part of a II – V – I sequence?

Here is a II – V – I sequence in Bb major featuring this same chord but now pointing towards its tonic. I’m using basic voicings with shells in the left hand.

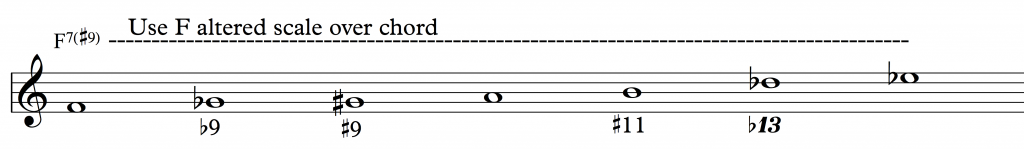

In this context, playing the F blues scale no longer works. Our solo is now more likely to be vertical (appropriate note choices over each individual chord). And this time the F7(#9) chord could, for example, support F altered scale:

If all this is beginning to get a little technical for some readers, I hope that the above illustrations demonstrate that one chord has different functions in different contexts and cannot simply be used because of its appealing sound in isolation.

A jazzy scale

And now for the scale that wins top prize for overuse. When I take on a new student we usually start with a basic 12-bar blues. This is not some test to expose weaknesses but rather an easy and usually relaxed meeting point during which a learning jazz pianist can solo while I provide a bass line. In most cases, however, I’m treated to a stream of six notes known as the blues scale.

As with my number 1 ‘jazzy’ chord, I have nothing against this scale other than its constant use. There are blues guitarists (that I won’t name) that have built a career out of endlessly running up and down this scale. This is why I choose to listen to the likes of Jeff Beck and Jimi Hendrix rather than those six-note wonders.

This time, rather than identifying chord function, here it’s a case of choosing other options. But I’ll start with an example of where you can use the blues scale to good effect other than in a blues: a minor II – V – I sequence.

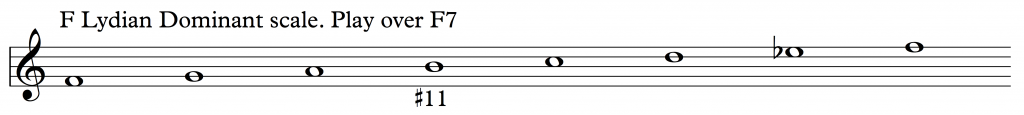

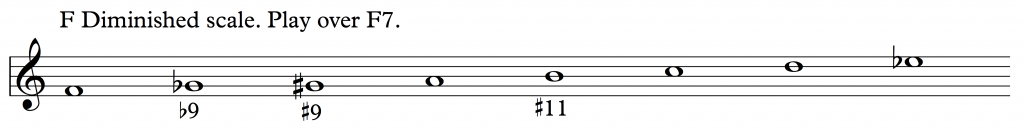

However, if you are soloing over, say, four bars of one dominant 7 chord, as in a basic blues, there are plenty more options than just running up and down the blues scale. Here are just two examples:

- The Lydian Dominant: This derives from the melodic minor scale a perfect 4th Or just sharpen the 4th of the Mixolydian mode.

- The diminished scale: When played over a dominant 7 chord, this scale repeats the alternate pattern of half tone, whole tone intervals.

When soloing over these scales, ensure that you emphasise the chord tones (A and Eb) on strong beats in order to bring out the harmony.

Playing Jazz, not playing jazzy.

So when my old jazz teacher (Howard Riley) said ‘stop playing jazz’ he was steering me away from ready-made sounds and licks, and towards creative exploration. Though tempting to dip into the jazz chocolate box of instant gratification, it is far more rewarding (and musical) to choose material that is relevant and in context, rather than trying to ‘play jazzy.’

I would suggest that soloing is like setting out on an exploration and being surprised by new discoveries. Mark Rylance, an eminent British actor, when asked about his acting technique, said something like this:

“I hate to see productions where the actors seem to know what is going to happen next. I actually prefer the feeling of slight unease and confusion as I receive the line. I can then work out how to respond in a more truthful manner.”

In other words, when playing jazz, rather than mechanically delivering his line, he becomes involved in the process of discovery, just as we do in normal conversation or when we solo. This is what I mean by playing jazz rather than playing jazzy.